I’ve decided to launch a dedicated series, which I called Longevium. There I’ll be sharing my insights and personal achievements in the realms of health, vitality, and longevity. Subscribe here!

Today, let’s talk about a rather intriguing metric known as VO₂max, also known as the maximal oxygen uptake. Modern physiology treats VO₂max as the gold standard for measuring physical fitness of a person.

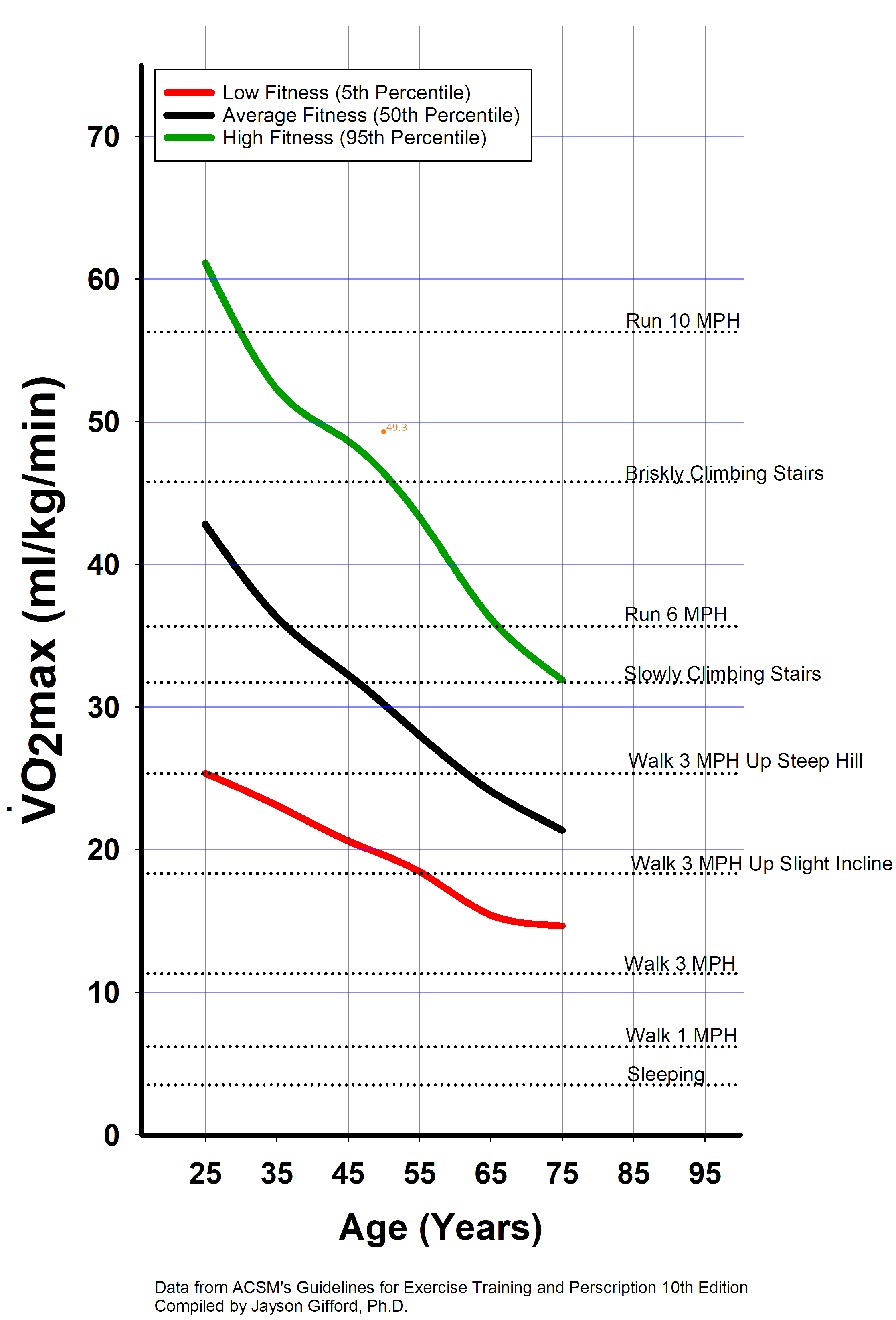

And here’s where it gets really interesting: if you know your VO₂max today, you can predict your fitness level 10, 20, 30 etc. years from now. Just take a look at this chart:

This graph, based on extensive data from the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM), shows how VO₂max declines with age across different fitness levels:

- Green line is the top 5% (the elite, fitter than 95% of the population);

- Black line is the median (half of people have a higher VO₂max, half lower);

- Red line denotes the bottom 5% (the least fit group).

It also shows the VO₂max levels required for various types of physical exertion. For example, running at 6 mph demands a VO₂max of about 36 ml/kg/min.

Now, let’s say you’re 25 years old with a VO₂max of 45 (a bit above average). At that fitness level, you’ll be able to maintain that pace until around age 35 — after that, not so much. By 60, even walking up a steep hill at more than 3 mph might proof out of reach.

Are you concerned yet?

VO₂max and Lifespan

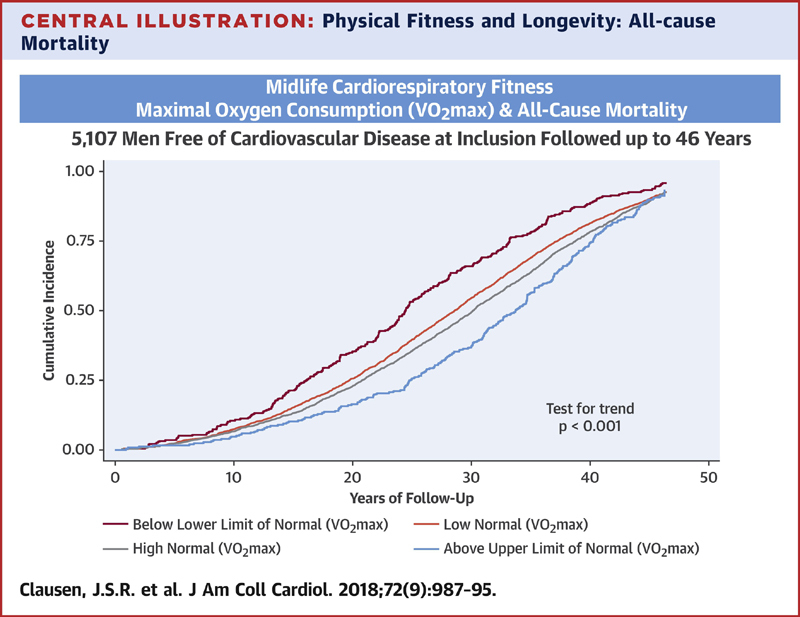

If not, let me introduce another graph:

This comes from a massive 46-year-long study tracking over 5,000 middle-aged males (aged ca. 48), correlating their VO₂max with overall mortality risk.

The chart shows the probability of dying over time for four different VO₂max levels (bottom 5%, lower 45%, upper 45%, and top 5%). While the risk of death after the 46 years is nearly certain (shocker!), at the 30-year mark (age 78), the difference between the fittest and least fit groups is more than twofold: 61% vs. 27%.

Moreover, the trend is crystal clear: the higher VO₂max = the lower risk of dying from literally anything. Science at its finest, bro.

But what is VO₂max, anyway?

VO₂max represents the maximum volume of oxygen (V = volume, O₂ = oxygen, max = maximum) your body can use per minute, normalized by body weight (hence the unit: ml/kg/min) to make it comparable between different persons.

It’s influenced by factors like heart performance, lung capacity, blood vessel throughput, muscle mass, and tissue quality. But the consensus among scientists is that VO₂max is the single best indicator of physical fitness: the higher it is, the fitter you are.

To measure it, researchers strap a subject into a fancy oxygen mask, put them on a treadmill, and gradually increase speed until oxygen uptake stops rising. Divide that oxygen volume by body weight, and voilà — your sentence VO₂max figure.

How to improve VO₂max

The charts above clearly show how fast VO₂max declines with age. Therefore boosting it is essential if you want to stay active and healthy as long as possible.

- First, a bad news: VO₂max improves very slowly; you literally have to work on it consistently for years.

- Now a good news: it declines also slowly. Even a couple of months off training won’t significantly drop your VO₂max.

- And there’s more: if you’re untrained, even small lifestyle changes can bring notable improvements.

Since VO₂max is essentially a measure of overall fitness, anything that improves fitness will also boost your VO₂max. That said, aerobic sports (running, swimming, cycling) are far more effective than, for instance, strength training.

How does it work?

Okay, so we know what VO₂max is. But how does oxygen uptake relate to fitness?

Increasing VO₂max results from improvements in your organs (heart, muscles, capillaries), as well as metabolism.

At a cellular level, oxygen is primarily used in mitochondrial metabolism. Mitochondria are tiny power plants in your cells that generate energy (ATP) by burning (oxidising) fat and lactate. Therefore, oxygen is the key ingredient in this process.

Training increases both the number and size of mitochondria, which directly enhances muscle tissue quality.

Optimizing VO₂max

So, the basic rule for improving VO₂max is simple: move more. Especially activities that elevate your heart rate and get breathing up — which is why running is much more effective than walking.

However, if you want a more structured improvement, you can apply this formula:

- 80% of your workouts should be low-intensity (below the so-called aerobic threshold).

- 20% should be high-intensity, ideally HIIT (high-intensity interval training).

My own VO₂max value

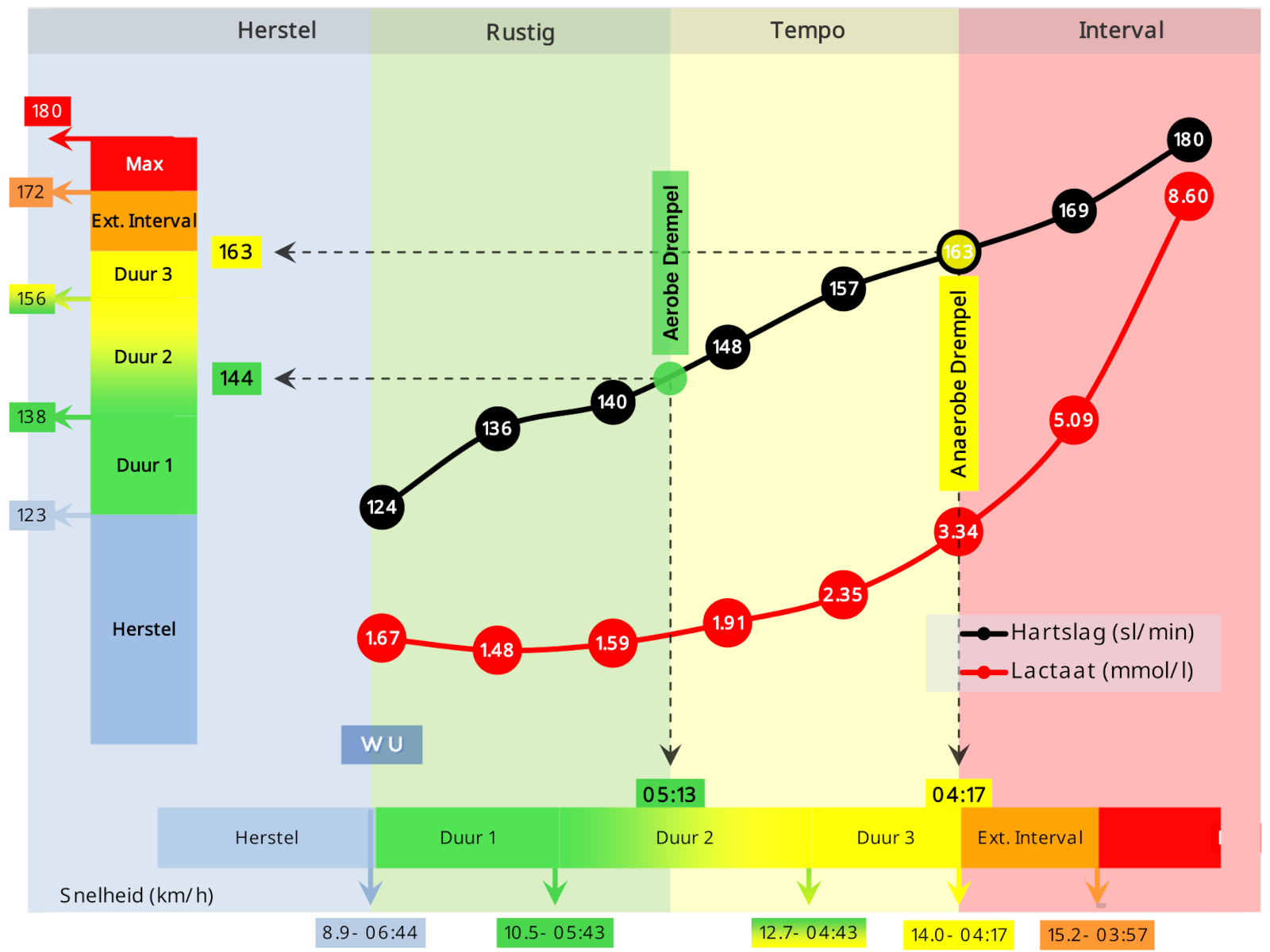

Recently, I took a VO₂max test at the Amsterdam Sports Medical Center. I was put on a treadmill, first having a low-pace warm up.

Then came the real test, with an oxygen mask on. I started off with leisurely 10 km/h for a few minutes, then the speed would increase by 1 km/h every three minutes. I was also measured for blood lactate levels on each step (more on the importance of lactate in a future post).

I managed seven speed increases, maxing out at 16 km/h — which felt as my absolute physical limit. Interestingly, my VO₂ peaked one step before the max speed and started to decrease afterwards, likely due to fatigue.

Here are my results:

- VO₂max: 49.3 ml/kg/min.

- Max heart rate: 180 bpm

- Max blood lactate: 8.6 mmol/l

- Aerobic threshold: 11.5 km/h, HR 144, 21 breaths/min

- Anaerobic threshold: 14 km/h, HR 163, 31 breaths/min

That first figure is the big one. On the initial VO₂max graph, I plotted my score (49.3). This puts me well above the 95th percentile, meaning my fitness is better than 97-98% of people my age (49 years old). My expectation was much lower!

However, among people tested at this medical center (many of them pro athletes), my result was even slightly below average.

Either way, now I know where I stand — and where to go next.

Final thoughts

Dear reader, do not procrastinate on your fitness. The sooner you start, the longer you’ll stay active, strong, and healthy. Keep tuned! ■

— world’s fastest URL shortener

— world’s fastest URL shortener

Comments