I’d like to show you a bit of northern Dutch summer in our damp off-season. Last June we’ve visited the city of Leeuwarden (Frisian: Ljouwert), situated in the very north of Holland. It is the capital city of the Friesland province, which is famous for its language that makes very little sense to an average Dutch.

Oldehove

One of the most noteworthy places in Leeuwarden is the leaning tower of Oldehove.

The tower is leaning more than the famous tower of Pisa. The cause was not discovered until recently, and it seems to be a very unfortunate coincidence.

The history of the Frisian epic fail is as follows. When in 1435 the city of Leeuwarden was formed by a fusion of three villages, Oldehove, Nijehove and Hoek, the demand for a bigger church arose. On May 28, 1529 the city council has given a mandate to the architect Jacob van Aaken to build a new church and a tower on the territory of the former Oldehove village.

Van Aaken commenced the construction at once. For him it was a kind of experiment, since he had never dealt with clay Frisian soil before. The legend has it that he began with a deep pit, which was later filled with layers of limestone. Furthermore, he make some other precautions—for instance, the tower had a very wide pediment.

And yet—all those tricks didn’t work out. The tower started to lean northwestwards when it was only ten metres (33 feet) high. Some contemporary specialist suggested the cause was the staircase tower (located just at the northwest side), whose 127 sandstone steps made it too heavy to sustain.

Three years into the construction Van Aaken died, reportedly of “chagrin”, and Cornelis Frederiks took over. He wasn’t any more fortunate, so the building was ceased after a year. In the years that followed the city tried to get the tower upright, but that didn’t work out either. The result was not only a leaning, but also crooked tower. It was also renovated several times, which cost the city quite a bit of money.

Only in 2005 the true cause of the failure was discovered. The tower was built on a slope of an old terp (mound), which once protected the area from flooding. So Van Aaken fell an innocent victim.

On the other hand, if the tower stood upright, it would be yet another Dutch tower, like ours in Amersfoort. Tourists would miss the opportunity to make funny forced-perspective photos.

The tower, which is nowadays 40 m (131’) high, can be climbed by 183 stone steps, spiraling up in a traditionally narrow shaft. The stair ends with a door with the text “PUSH STRONGLY” on it:

The tower’s top is 1.68 m (5’ 6") off the vertical, which translates to 2° given its height. If you’re not scared by these numbers, I’d recommend to get to its top to see the panorama of Leeuwarden. The city is magnificent in the summer.

And quite diverse. Some high-rises stick out of the traditional Dutch tiled roofs:

The top of the tower is equipped with an observation deck with a glass floor.

Right beside the tower there’s a sanded football field:

A panoramic view on the city:

Wilhelmina’s tree

Like any other Dutch municipality, the city has a tree planted when the Queen Wilhelmina (1880–1962) acceded to the throne on August 31, 1898:

Mata Hari

Apart from its ever-leaning tower, Leeuwarden is known as a birth place of the dancer, courtesan and spy Mata Hari (real name Margaretha Geertruida Zelle). A humble monument was installed here on her 100-year anniversary (1976):

The Big Church and the Jewish Monument

From secular concerns to spiritual again. The Big Church (Grote Kerk a.k.a. Jacobijnerkerk) was built in the end of XIII — beginning of XIV century:

Families of the Stadtholders (stadhouders) had the privilege of an own church gate, later named “The Orange Tree” (De Oranjeboom):

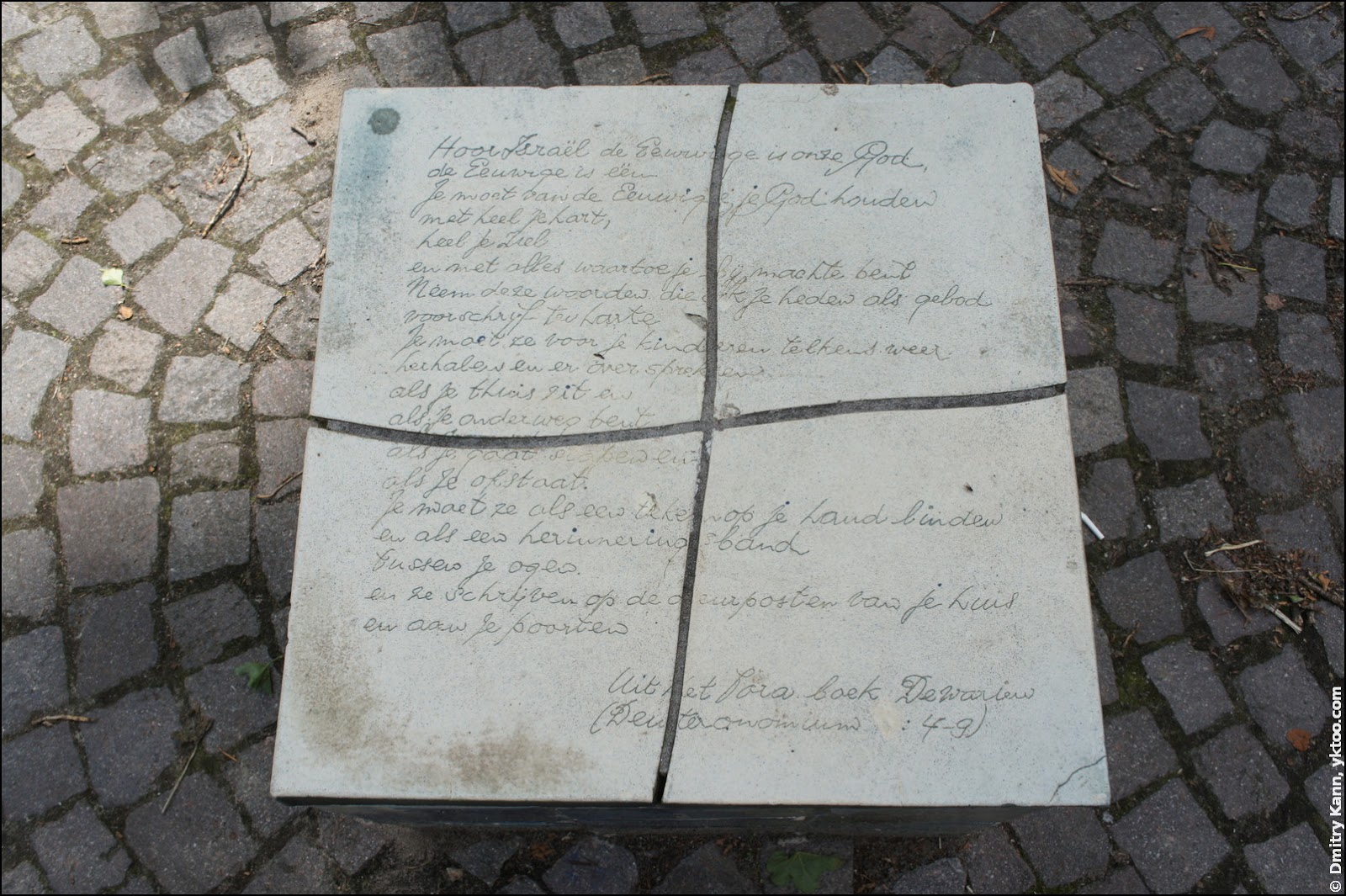

Near by the church is Jodenmonument, the Jewish Monument, commemorating the Jews of Leeuwarden murdered by the nazis during the World War II.

The walls are inscribed with the names of the deceased (550 out of 655 were killed by nazis) and texts from various community’s documents.

One of the oldest houses in the city named Keimpema Stins (1350) looks quite good for its age:

Boshuisen Almshouse

This building (Het Boshuisengasthuis) was built by the couple Anna and Philip van Boshuisen in 1651 for old single women, regardless of their religion. It looks much better than what I would imagine at the word “almshouse”:

Very clean and neat. There are quite a few pets.

Some of them are well-fed:

Blokhuispoort

This cheerful building (a group of buildings, actually) called Blokhuispoort was built in 1499 and then served as a prison for man convicted for five years and more:

It’s a museum of 500 years of Frisian jail history. There’s also an online version available.

Rock’n’roll in the boat

Canals in the downtown resemble ones of Amsterdam.

At one of them a band was playing rock’n’roll tunes in the boat.

I was very impressed by the powerful sound these chaps made in such an unstable setting: here’s a video of one of the songs.

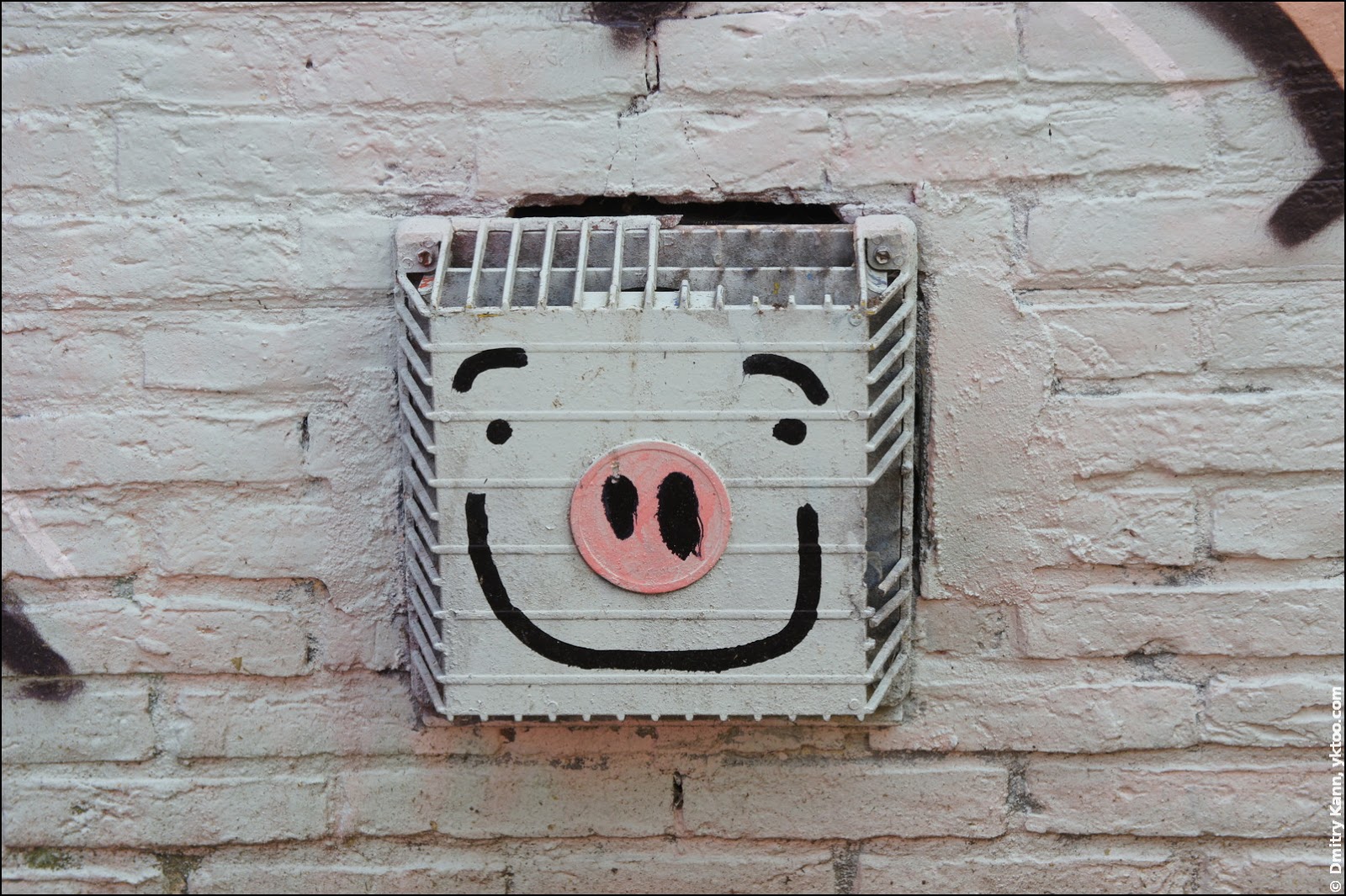

Graffiti in Ruiterskwartier

There’s a whole block painted with graffiti—Ruiterskwartier.

And it’s completely deserted. The most impressive things:

Hogweed taller than a human in some places suits the surrounding well.

Other artifacts

The city centre makes the impression of an outrageously well maintained place.

Frisians are proud of their history:

A funny painting on display:

But this riddle cost me some effort to solve:

’t Is avond in Siberië En nergens is een leeuw

Which translates as:

It’s evening in Siberia, And a lion is nowhere

But some Dutch friends and Google helped me. It’s a verse from a very long and old Dutch song called Dodenrit (“Suicidal Ride”). It’s sung in 1974 by Drs. P (video), and it’s a quite cynical, or black-humored, piece. It’s a story of a family that rides a troika in the direction of the Siberian city of Omsk in a very cold winter. They are being chased by wolves, so they decide to dump their kids one-by-one to get rid of wolves. Yet the plan doesn’t work out and the end is anything but happy.

Now, the challenge was to find the missing link between the song and this pointer. As far as I could conclude, the idea is that “lion is nowhere”, i.e. the name of the city is commonly wrongly associated with “lion” (leeuw), though in fact it’s derived from the old Frisian Lintarwde and later Liiewardensis.

That’s all folks. If you happen to be in the north here, do pay a visit to the sunny Leeuwarden.

— world’s fastest URL shortener

— world’s fastest URL shortener

Comments